Why Jenrick left

Notes on the harbinger, and the data that made his departure inevitable.

“He’s literally trying to be me without the personality.” It was a Saturday in late June and Nigel Farage was bellowing into his car phone while complaining about the signal (not what it used to be). I was writing a profile of Robert Jenrick, who still aspired to rival Farage at the time. Reform’s leader was only too willing to define him.

“I’ll give him credit for some good videos, for trying hard,” he said. “What he can’t get away from is his record of the last 14 years. The fact is the Conservatives were the ones who opened up the doors and empowered the gangs. I was doing videos of migrant hotels in 2020. They will not be forgiven for the Boriswave. The trust has completely gone.”

He described his erstwhile rival as “an absolute waste of space: ineffective, ineffectual, [and] not a particularly convincing speaker.” He mused on Tory Party rivals. “I don’t see anybody that’s going to come through the ranks and capture the public’s imagination. I don’t think he [Jenrick] has the charisma for it.”

“I’m allowed to change my mind you know,” Farage said on Thursday with a chastened Jenrick sitting beside him, introduced post haste. “I’m a bit like Zia [Yusuf]. I don’t trust any of them naturally,” he said of defecting Tories. “They have to prove to me that they are genuinely repentant.”

He referred to Jenrick as “this guy”, praising his “journalism” and video-making. He was less enamoured by his output in June. (“Twitter’s not what it was,” he said then. “It’s now really a bit of a right-wing echo chamber. What’s he getting on Facebook? What’s he getting on Instagram, TikTok?”)

Still, Farage was happy to take him. “I’m getting people in who are apologetic, indeed ashamed, of what they’ve done in the past, who recognise what went wrong, and are determined to get it right,” he told the small clapboard room full of journalists and TV cameras high up in Millbank Tower. He would, like Christ, welcome the repentant, if they “promise to put their shoulders to the wheel and propel us forward.”

The brutality of the new power balance between the two men was made clear shortly thereafter. Jenrick promised he would indeed put his shoulder to the wheel, echoing Farage’s phrase and looking to him as he did. Farage started straight ahead and called out the next question. When Jenrick began to reply to another, Farage talked over him, moving on. He could be generously described as sparing Jenrick the need to explain himself.

Jenrick’s resignation speech leaked after he left a copy on the desk in his Westminster office on Wednesday and went to shadow cabinet. The door was unlocked. Someone wandered in and took a picture which they sent to Kemi’s office. It is possible that an MP came to see Jenrick, knocked on his door, found the room empty, walked in, and leaked the speech. But those around Jenrick think that too brazen to believe.

It’s easy to focus on the leverage Jenrick lost by being forced to leave rather than choosing to depart, but I’m not sure the manner of his entrance will matter for long within Reform. The election is three and a half years away: too far for him to have been promised the chancellorship, a job Zia Yusuf may be better suited to in any case.

Jenrick would fit at the Home Office. It’s the job his former friend Rishi Sunak declined to give him in 2023. Sunak’s refusal to promote him – he had been immigration minister inside the department, and knew its failings well – prompted Jenrick’s subsequent resignation. The job went to James Cleverly, whose bluff centrist instincts still represent too great a part of the Tory Party for Jenrick to remain in it.

“He realised the Tory Party was not fixable,” says a member of his team. “He had seen there were so many people in the Party that don’t understand how broke the country is, and the scale of change that’s needed. He had started giving speeches that a Reform MP would give.”

Jenrick has talked before of how he spent his first eight years in politics (2014-2022) assuming that the system basically worked, and his job was to fit within it. Then he entered the Home Office and realised the system didn’t work at all. The department, in his telling, had no idea of how to control the nation’s border or even of who was in the country; the data was partial and months-late, and no one seemed to mind.

After leaving the Home Office and beginning his political and personal reinvention – it’s hard now to imagine him as anything other than a slim man who posts pictures of himself hiking – he began to discover much else that he deemed broken too. He realised that the scandals emerging now under Labour – from the Chagos deal to Alaa Abd El-Fattah’s celebrated release – had their origins under the Tories.

“It’s a Tory prisons crisis,” one staffer says, reflecting on Jenrick’s shadow cabinet brief until this week. “They increased sentences without increasing places.” Jenrick will no longer need to hide such beliefs about the past now that he is with Farage.

Here’s a line you can expect to hear from Jenrick. He will say that he has seen inside the Tory Party, and it is even worse than you think. He will say that Kemi’s claim to “deep thinking” is a myth, that her vaunted policy commissions are Potemkin affairs, that Mel Stride’s mooted budget savings were drawn up on the back of a packet, and the party can no longer claim to be a seriously run organisation.

All of those criticisms may equally apply to the party he is joining, but it’s not an advantage the Tory Party can claim to enjoy. When its leaders attempt to do so, Jenrick will cry foul. Voters to the left of centre will pay no attention – they prefer Farage to a turncoat – but some wavering voters on the right may heed his words.

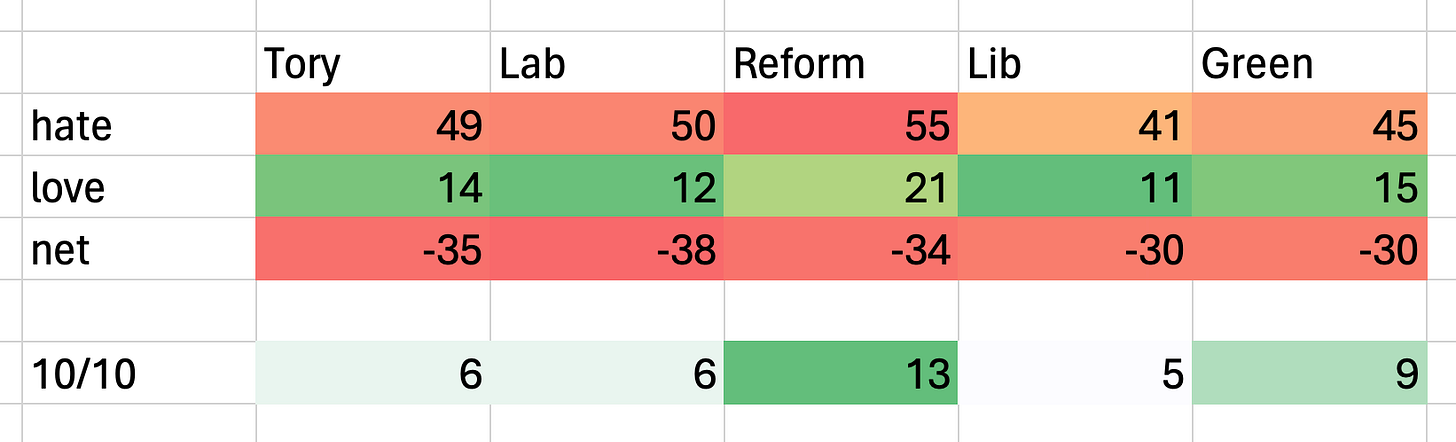

Here’s some harder data to understand where we are. Take a look at this recent YouGov poll, in which voters were asked to rank how likely they are to vote for a party on a 0-10 scale. I count a score of 0-2 as ardent opposition and 8-10 as strong support.

First, everyone is unpopular. Second, Reform is the most intensely disliked party – 55 per cent of voters would never vote for them – but they are only marginally more hated than Tory and Labour. That’s notable given much tactical voting is likely to matter in 2029, and a pervading sense that Farage alone risks being stopped by it.

There is a counterpoint – a positive one for Jenrick: Reform is also the party with the most intense support. 21 per cent of voters are enthusiastic about voting for them. Only 14 per cent feel that way about the Tories. In the final line of my table you can see the source of that gap: Reform have a 7-point edge among 10/10 voters – the most intensely supportive.

Something else stands out in the data. If you look at the four issues of most relevance to voters – the economy, immigration, the NHS, and (unusually) defence – a party has a commanding lead on only one of the issues. Would you like to guess who?

The Tories lead by 2 points over Reform on defence. Labour trail by 6.

Labour are 6 points ahead of the Tories on the NHS. Reform trail by 8.

The Tories have a 7-point lead over Reform on the economy. Labour trail by 9.

Those fights are all close. But one isn’t:

Reform lead by 24 points over Labour on immigration. The Tories trail by 26.

That, at root, is why Jenrick left. Immigration is by far the most important issue to voters on the right, and Jenrick has come to feel it is the most important issue to him. He has gone from a party that 8 per cent of voters trust on the issue to one that 34 per cent of voters trust. Viewed in such terms, it’s suddenly strange he waited so long.

Postscripts

One Tory grandee, no fan of Jenrick’s, gave him his due when we spoke on Thursday: “When Jenrick goes and does something, there’s a minor crackle of excitement. When he speaks at the despatch box, he puts on a good show.” But, he added: “When the good lord made Robert, he gave him many virtues – intelligent, good-looking, humorous, a rich wife. What he didn’t give him were either loyalty or patience.”

Kemi is doing well, the MP said, because “the lads like her for doing better at PMQs, stamping all over Starmer. I think Kinnock found Thatcher very hard to handle at the despatch box [too], and there’s something similar with Kemi and Starmer. He’s tried patronising her, and that doesn’t work.”

If you add up the strong support for each of the five parties in the table above, you get 73 per cent. That leaves around 20 per cent of the electorate who are in play. (The remainder will vote for nationalist or other parties.) The question in British politics until 2029 is how everything will play with this 20 per cent. I’m one of them: are you?

Here’s the July profile. Patrick Maguire wrote up flying with Farage on Thursday here.